Using herb and flower infusions in soap can add a little something extra special to your soap. I love using both chamomile and calendula (marigold) infusions in my soap. Both impart a pretty butter yellow to the finished soap. There is a slight scent in the oils, too, but I find that scent doesn’t usually survive the saponification process, and I have used fragrances and essential oils successfully in soaps with infused oils.

Using herb and flower infusions in soap can add a little something extra special to your soap. I love using both chamomile and calendula (marigold) infusions in my soap. Both impart a pretty butter yellow to the finished soap. There is a slight scent in the oils, too, but I find that scent doesn’t usually survive the saponification process, and I have used fragrances and essential oils successfully in soaps with infused oils.

There are a couple of techniques you can use for infusing oils. You can put the flowers or herbs in a jar, pour your oil over them, and let them infuse for several weeks, but I like the slow cooker method, mainly because it’s quicker, and I’m impatient.

I purchased these handy “tea bags” from Bramble Berry (who is not sponsoring me; I just like the product). While you can pour the oils directly over the botanicals, I have found it is pretty messy, and you have to strain the oil later. The tea bags allow the botanicals to infuse the oil without making a mess. I try to use about ½ to 1 ounce of botanicals (which is a lot more than you’d think—they are light). I put the botanicals in the tea bags and seal them closed with an iron. Then I put them in a jar, I pour olive oil over the filled tea bags. I put a few inches of water in my slow cooker, turn it on low, and gently lay my jar in the water. I let the oil infuse in the heat of the slow cooker for about five hours, turning the jar over every once in a while (be careful; it’s very hot). The jars can be hard to open afterward, but I have a nice infused olive oil to use in my soap when I’m done.

If you want to try out infused oils in your own soap, check out this recipe for a one-pound batch.

- 162 grams distilled water

- 59 grams lye

- 170 grams olive oil

- 106 grams coconut oil

- 106 grams palm oil

- 22 grams shea butter

- 21 grams castor oil

- 25-28 grams fragrance or essential oil optional

- 2 large tea bags

- 1/2 ounce dried calendula petals

- Put the calendula petals in the tea bags and iron edges to close.

- Place the calendula bags into a large jar.

- Put the jar on a scale and tare the scale. Add a bit more olive oil than you need. This recipe calls for 170 grams, but some of the oil will be soaked up by the calendula petals and the bags; it will be hard to get every last drop out again.

- Screw the lid tightly on the jar and place it in a slow cooker on low. Let the oil infuse from 2-5 hours.

- Set the infused oil aside to cool. It will be too hot to soap with right after the infusion.

- When your infused oil is cool, prepare your water and lye. Measure out 162 g distilled water and set aside. Measure out 59 g lye in a separate container and set aside. Carefully add the lye to the water and stir until it is dissolved. Set the lye solution aside to cool.

- Measure out your hard oils (106 g coconut, 106 g palm, and 22 g shea butter) and melt them down.

- Add 170 g infused olive oil and 21 g castor oil to the melted hard oils.

- Once your lye water has cooled (I usually combine my oils and lye water at about 100ºF), add the lye water to the oils and blend to a light trace.

- Add your fragrance (optional) and either whisk in or stick blend carefully.

- You can add calendula petals to your top for extra decoration. Calendula petals keep their color in cold process soap, so you can even add it to the soap itself.

Whether or not the soothing qualities of calendula survive the saponification process is up for debate, but the infusion does impart a nice, light color to the soap. Why not try it and see if it works for you?

I completely scrapped my other recipe. I used two ounces of carrot baby food, removing two ounces of water from my recipe and reduced the total amount of liquid in the recipe from 38% (which

I completely scrapped my other recipe. I used two ounces of carrot baby food, removing two ounces of water from my recipe and reduced the total amount of liquid in the recipe from 38% (which

Ingredients

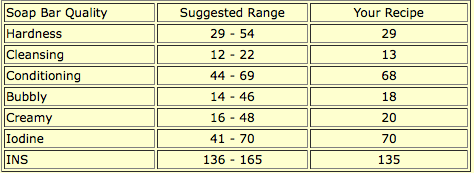

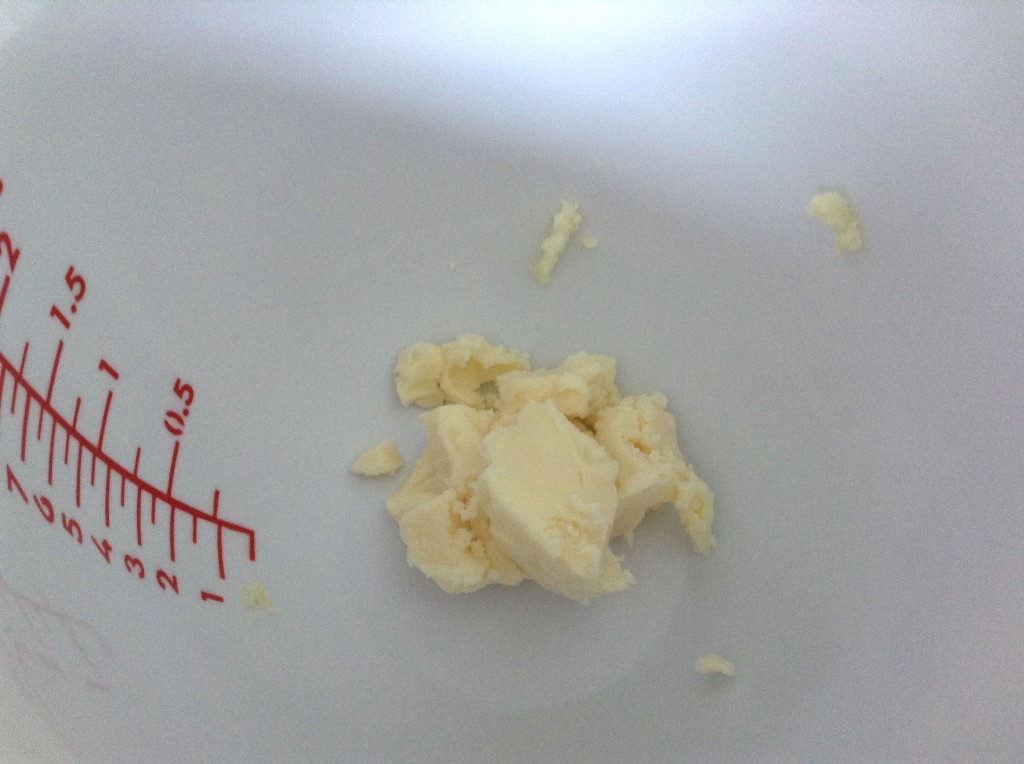

Ingredients Mango butter is truly wonderful. It is similar to shea butter in some respects in that it has a significant amount of unsaponifiables, meaning that more of the conditioning and moisturizing qualities of the butter make it through the saponification process. It also contributes to a creamy lather.

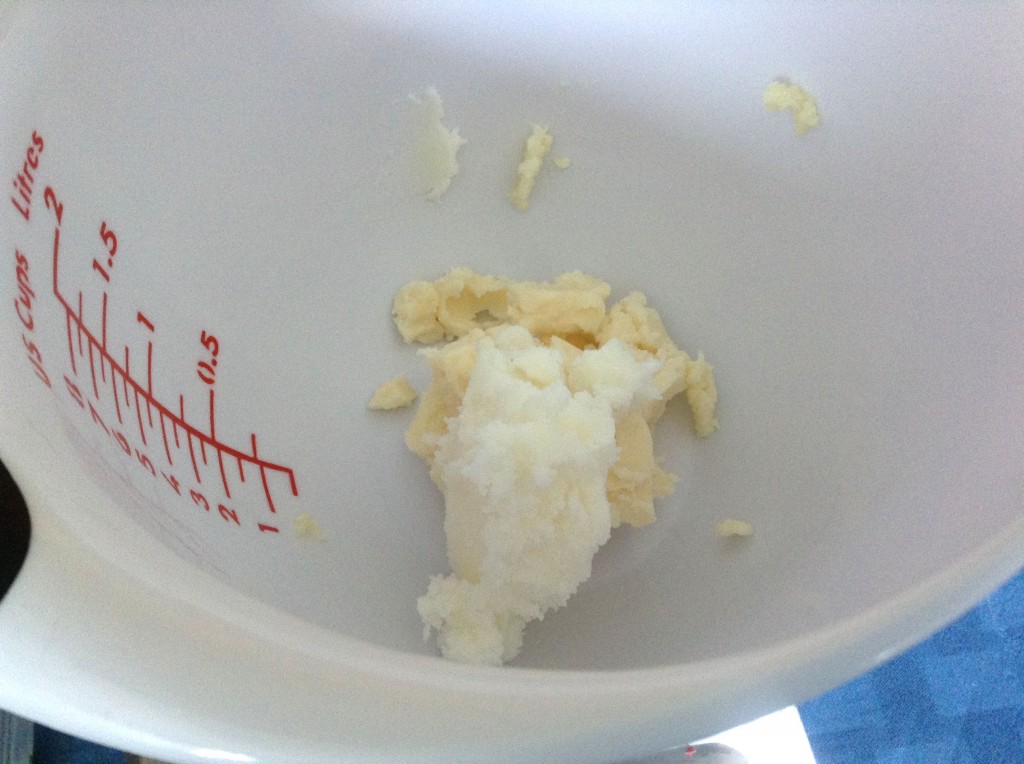

Mango butter is truly wonderful. It is similar to shea butter in some respects in that it has a significant amount of unsaponifiables, meaning that more of the conditioning and moisturizing qualities of the butter make it through the saponification process. It also contributes to a creamy lather. I added the shea butter to the mango butter. I use shea butter and/or cocoa butter in almost all of my soaps because I love what it does for skin. It does speed up trace, so be careful.

I added the shea butter to the mango butter. I use shea butter and/or cocoa butter in almost all of my soaps because I love what it does for skin. It does speed up trace, so be careful. In with the coconut oil. It’s so hot here today that it’s completely melted already. Actually the mango butter was kind of soft as well. It’s usually a little harder (and almost brittle) than it was today. Coconut oil is great for bubbles—it contributes to fluffy lather and cleansing as well as bar hardness. I use coconut oil in almost all of my soaps.

In with the coconut oil. It’s so hot here today that it’s completely melted already. Actually the mango butter was kind of soft as well. It’s usually a little harder (and almost brittle) than it was today. Coconut oil is great for bubbles—it contributes to fluffy lather and cleansing as well as bar hardness. I use coconut oil in almost all of my soaps. The last hard oil is palm oil, which I use because it contributes to bar hardness, stable lather, and conditioning. I use it in a lot of my soaps.

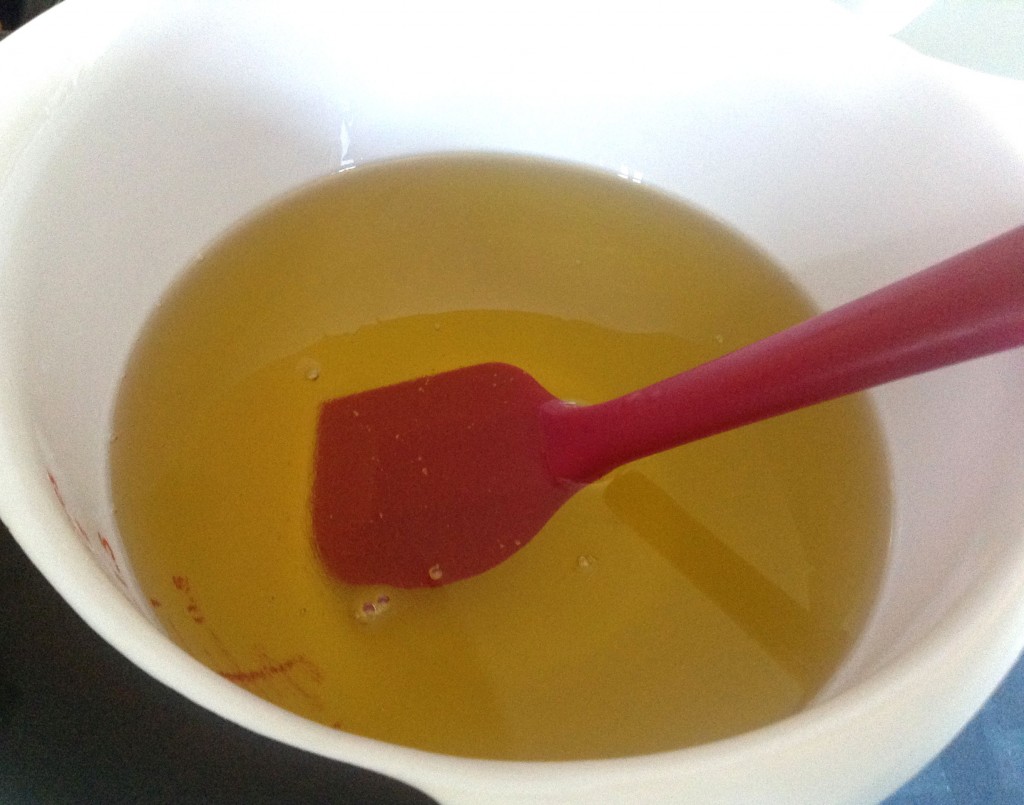

The last hard oil is palm oil, which I use because it contributes to bar hardness, stable lather, and conditioning. I use it in a lot of my soaps. A quick word about olive oil: you can use any grade of olive oil in soap, but I always use pure golden olive oil. I don’t think it’s necessary to use extra virgin olive oil in soapmaking. In fact, it’s not different enough from pure golden olive oil to warrant its own category in SoapCalc, though olive oil pomace is. I personally don’t use pomace because pure golden olive oil is available at my local discount membership warehouse for a really good price (and no shipping). I use olive oil in every single soap I make. It’s highly conditioning and contributes to stable lather and bar hardness. I believe it to be the single best soaping oil there is.

A quick word about olive oil: you can use any grade of olive oil in soap, but I always use pure golden olive oil. I don’t think it’s necessary to use extra virgin olive oil in soapmaking. In fact, it’s not different enough from pure golden olive oil to warrant its own category in SoapCalc, though olive oil pomace is. I personally don’t use pomace because pure golden olive oil is available at my local discount membership warehouse for a really good price (and no shipping). I use olive oil in every single soap I make. It’s highly conditioning and contributes to stable lather and bar hardness. I believe it to be the single best soaping oil there is.

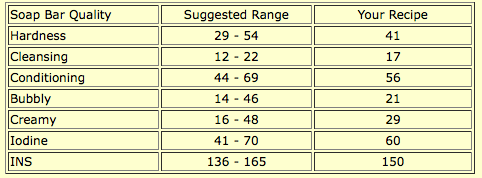

Working with milk requires a bit more effort than working with water. I use a stainless steel pot because if I need to quickly cool it down the mixture, stainless steel is a better conductor (hot or cold) than plastic or glass. I also add the lye to the milk just a little at a time and stir until the lye is dissolved. Then I add more. It can take a little while. Once all the lye was added, and I was relatively sure the all of it had dissolved in the milk, I added the sodium lactate to the lye mixture and stirred well to dissolve it.

Working with milk requires a bit more effort than working with water. I use a stainless steel pot because if I need to quickly cool it down the mixture, stainless steel is a better conductor (hot or cold) than plastic or glass. I also add the lye to the milk just a little at a time and stir until the lye is dissolved. Then I add more. It can take a little while. Once all the lye was added, and I was relatively sure the all of it had dissolved in the milk, I added the sodium lactate to the lye mixture and stirred well to dissolve it. I checked the temperature of the lye mixture, and it was about 82°F. Pretty good. I don’t like it to rise above 90°F. If it starts to become too warm, I put the pan in a cool water bath to bring the temperature down.

I checked the temperature of the lye mixture, and it was about 82°F. Pretty good. I don’t like it to rise above 90°F. If it starts to become too warm, I put the pan in a cool water bath to bring the temperature down. I stick blended until a very light trace, then I added the honey. Honey will accelerate trace, so make sure you add it at a light trace, or you may find you have gone too far with the stick blending. When I use honey in soap, I mix it with an equal amount of distilled water. In this case, I used 1.5 t of honey, so I mixed it with 1.5 t of water. Then I microwave the honey for a very short time—only 5-10 seconds. I stir until it dissolves in the water. I find that I have fewer issues with scorching, overheating, and

I stick blended until a very light trace, then I added the honey. Honey will accelerate trace, so make sure you add it at a light trace, or you may find you have gone too far with the stick blending. When I use honey in soap, I mix it with an equal amount of distilled water. In this case, I used 1.5 t of honey, so I mixed it with 1.5 t of water. Then I microwave the honey for a very short time—only 5-10 seconds. I stir until it dissolves in the water. I find that I have fewer issues with scorching, overheating, and  I blended to a pretty thick trace, then poured the soap into my 10-inch silicone loaf mold, which was the perfect size for this recipe. Bramble Berry recommends using sodium lactate to make it easier to remove soap from this mold, and in any case, sodium lactate adds a nice silky feel to soap.

I blended to a pretty thick trace, then poured the soap into my 10-inch silicone loaf mold, which was the perfect size for this recipe. Bramble Berry recommends using sodium lactate to make it easier to remove soap from this mold, and in any case, sodium lactate adds a nice silky feel to soap. Like Cee, I spooned soap on the top after doing a little bit of sculpting, but I didn’t think my tops were as pretty as hers, so I experimented a bit with a skewer to create a slightly different design.

Like Cee, I spooned soap on the top after doing a little bit of sculpting, but I didn’t think my tops were as pretty as hers, so I experimented a bit with a skewer to create a slightly different design. I spritzed it with 91% isopropyl alcohol, which might not have been strictly necessary since I didn’t choose to gel the soap, but it can’t hurt anyway. Isopropyl alcohol can help prevent soda ash on the tops of soap, but it’s not 100% effective.

I spritzed it with 91% isopropyl alcohol, which might not have been strictly necessary since I didn’t choose to gel the soap, but it can’t hurt anyway. Isopropyl alcohol can help prevent soda ash on the tops of soap, but it’s not 100% effective. The cut soaps smell wonderful. I am going to let them have a nice long cure and give them to family and friends for Christmas.

The cut soaps smell wonderful. I am going to let them have a nice long cure and give them to family and friends for Christmas.