Babies have sensitive skin. I looked up the ingredients for a popular commercial soap used on babies, and this is what I found:

Water, Cocamidopropyl Betaine, PEG-80 Sorbitan Laurate, Sodium Laureth Sulfate, PEG-150 Distearate, Tetrasodium EDTA, Sodium Chloride, Polyquaternium-10, Fragrance, Quaternium-15, Citric Acid, Sodium Hydroxide.

I was not really sure what some of of this stuff was, so I did a little Internet research.

- Cocamidoproply Betaine is “is an organic compound derived from coconut oil and dimethylaminopropylamine.” (Wikipedia)

- PEG-80 Sorbitan Laurate is a surfactant, emulsifier, and fragrance ingredient.

- Sodium Laureth Sulfate is a detergent and surfactant.

- PEG-150 Distearate is a surfactant, thickening agent, and emulsifier.

- Tetrasodium EDTA is a “chelating agent, used to sequester and decrease the reactivity of metal ions that may be present in a product” (Environmental Working Group)

- Polyquaternium-10 is a “Antistatic Agent; Film Former; Hair Fixative” (Environmental Working Group)

- Quaternium-15 is an ammonium salt used as a preservative in cosmetics (Wikipedia)

I am not sure it can properly be called soap, which is fine, because the manufacturer doesn’t call it soap, either. But all I have to say is… wow. I used this on my children. The safety of the ingredients has been called into question by various watchdog groups, and I realize they sometimes have an agenda, but this list of ingredients actually scares me. I realize that sometimes soapmakers are unfairly critical of commercial soaps’ use of chemical names. Everything on earth is made of chemicals, and commercial soapmakers have different regulations by which they must abide. But there is little in this list I could recognize from my own soapmaking experience except water, sodium hydroxide, citric acid, and sodium chloride.

Another popular baby soap lists the following ingredients:

vegetable soap base, parfum (fragrance), butyris lac (buttermilk powder, babeurre en poudre), avena sativa (oat) kernel flour, CI 77891 (titanium dioxide), limonene

I don’t want to turn this post into an analysis of how bad commercial soaps are for you (because I’ve written that post before), but I want to know what’s in that vegetable soap base, too. The other ingredients I get (and use). Limonene is a fragrance ingredient. This soap is probably gentle, but it does have fragrance and titanium dioxide, which I would leave out of a soap formulated especially for babies. Still, there is nothing terribly alarming in the list of ingredients, and if you’re going to use a commercial soap, this one is probably better for baby than the previous one.

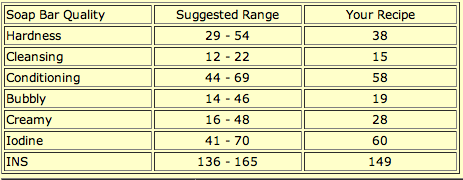

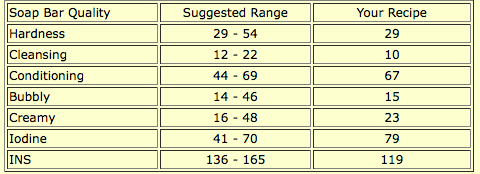

Babies have the most sensitive skin, and a great deal of thought should be given to formulating a soap recipe that is as gentle and mild as possible. My baby soap recipe is 75% olive oil, 20% coconut oil, and 5% castor oil. Olive oil is one of the most conditioning oils, and pure Castile soap is excellent for the skin. The coconut oil and castor oil boost the lather a bit without detracting from the soap’s mildness or conditioning qualities. Here is SoapCalc’s quality assessment:

As you can see, the conditioning quality is near the upper suggested limit, while the cleansing quality is near the suggested lower limit. This recipe is actually a tried-and-true baby soap recipe you have probably seen on other soapmaking websites.

As you can see, the conditioning quality is near the upper suggested limit, while the cleansing quality is near the suggested lower limit. This recipe is actually a tried-and-true baby soap recipe you have probably seen on other soapmaking websites.

But what about other skin types? How do you formulate a facial soap for mature or sensitive skin? Oily skin?

You really need to research oils and their properties. For my Carrot Silk Facial Soap, I left out scent and formulated the recipe for sensitive skin: olive oil, water, sustainable palm oil, coconut oil, sodium hydroxide, palm kernel oil, pureed carrots, castor oil, sunflower oil, goat milk, kaolin clay, tussah silk.

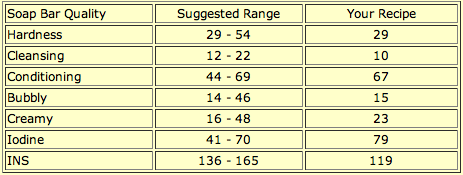

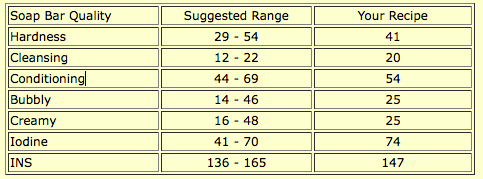

Here is SoapCalc’s assessment of Carrot Silk Facial Soap:

As you can see, the conditional quality and cleansing qualities are mid-range, which is perfect for most people who want a facial soap that will wash away the dirt and makeup without stripping the skin. The addition of carrots, goat milk, kaolin clay, and silk to the soap add qualities that SoapCalc cannot quantify.

As you can see, the conditional quality and cleansing qualities are mid-range, which is perfect for most people who want a facial soap that will wash away the dirt and makeup without stripping the skin. The addition of carrots, goat milk, kaolin clay, and silk to the soap add qualities that SoapCalc cannot quantify.

My Lavender Chamomile Facial soap has the following ingredients: water, chamomile-infused olive oil, rice bran oil, avocado oil, coconut oil, sodium hydroxide, apricot kernel oil, shea butter, castor oil, lavender essential oil, pink rose clay, buttermilk.

I chose chamomile, olive oil, rice bran oil, avocado oil, apricot kernel oil, and shea butter specifically for their conditioning properties.

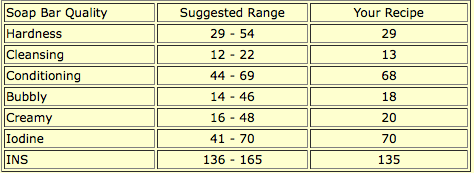

A glance at SoapCalc’s assessment reveals many quality numbers off the scale: cleansing is lower than recommended, iodine is higher, and INS is lower. Still, this recipe makes a very nice soap. The low cleansing number makes it especially good for dry, sensitive, or mature skin, as does the high conditioning number. Though this soap has fragrance, it is a lavender essential oil, and this blog post by Robert Tisserand does a good job of describing some of lavender’s benefits, even including research citations.

A glance at SoapCalc’s assessment reveals many quality numbers off the scale: cleansing is lower than recommended, iodine is higher, and INS is lower. Still, this recipe makes a very nice soap. The low cleansing number makes it especially good for dry, sensitive, or mature skin, as does the high conditioning number. Though this soap has fragrance, it is a lavender essential oil, and this blog post by Robert Tisserand does a good job of describing some of lavender’s benefits, even including research citations.

But what about oily skin? I admit I haven’t made this soap yet, but I did some research and formulated a recipe with the following ingredient list: coconut milk, coconut oil, neem oil, sunflower oil, sodium hydroxide, sustainable palm oil, rice bran oil, castor oil, bentonite clay, activated charcoal, tea tree essential oil, rosemary essential oil.

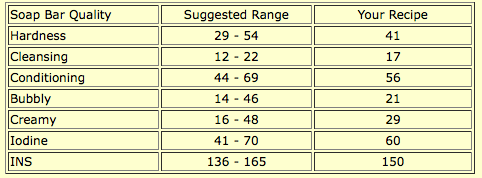

Coconut oil is more cleansing, and neem oil has antiseptic and anti-fungal properties that make it helpful in combating acne. Bentonite clay and activated charcoal are said to be good for oily skin, as are tea tree oil and rosemary oil. Here is SoapCalc’s assessment:

The numbers all fall within the suggested range, but this soap is more cleansing than the other facial soaps, and the iodine is higher than suggested. It should clean the skin without overdrying, which many commercial acne preparations do (which causes the skin to compensate by producing more oil, which continues a vicious cycle).

The numbers all fall within the suggested range, but this soap is more cleansing than the other facial soaps, and the iodine is higher than suggested. It should clean the skin without overdrying, which many commercial acne preparations do (which causes the skin to compensate by producing more oil, which continues a vicious cycle).

The quality numbers are a good guide, but the key is doing research into the oils and additives you are using, and determining what benefits those ingredients will add to your soap. Soapmakers have to be careful not to make claims about their soap due to FDA regulations. “True” soap is not regulated by the FDA, and ingredients do not need to be listed on soap labels. According to the FDA:

If a cosmetic claim is made on the label of a “true” soap or cleanser, such as moisturizing or deodorizing, the product must meet all FDA requirements for a cosmetic, and the label must list all ingredients. If a drug claim is made on a cleanser or soap, such as antibacterial, antiperspirant, or anti acne, the product is a drug, and the label must list all active ingredients, as is required for all drug products.

I think some soapmakers wrongly interpret this to mean that they cannot make claims about the qualities of their soap. My understanding, based on this statement, is that you can claim your soap moisturizes if you list the ingredients. The following are requirements for a cosmetic label:

- Identification of the product (which indicates its use)

- Net weight

- Name and address of manufacturer

- Warnings and cautions (if any)

- Ingredients in descending order of amount

Where you might run into trouble is labeling a soap as anti-acne, which means you must comply with FDA labeling requirements for drugs. See this article for information about such labels. My understanding, based on reading this article, is that if you comply with these very specific requirements for labeling, you can make claims, such as anti-acne, about your soap. I do not plan to make any such claims when I make my soap. But based on what I’ve read, I believe I’m in the clear to say it’s formulated for oily skin types.

If you’re looking to formulate your own recipes for various skin types, take a look at resources for oil properties. Two of my favorites are Summer Bee Meadow’s Properties of Soapmaking Oils and About.com’s Candle and Soap Soap Making site’s Qualities of Soap Making Oils article. Research various clays, essential oils, and other additives, such as botanicals, so that you can learn about their benefits for the skin. Do they work better on dry skin, or oily skin? What qualities do they have?

I have put a great deal of research into each of the ingredients I’ve included in these facial soaps, and based on the testing for Carrot Silk Facial Soap and Lavender Chamomile Facial Soap, it appears as though the research has resulted in soap that really does what I hoped they would do.