At this point, I’ve read several good books about making soap. I have to put Anne L. Watson’s Smart Soapmaking and Milk Soapmaking at the top of the pile. Both of these books are practical, no-nonsense books that should get any beginner on way to making soap. Both books include several tried and tested recipes that are easy for beginners. Most soap-making books just include one basic recipe with variations. Those books can be nice, but they’re not very helpful for beginners who want to try different combinations of oils to see what will happen. Another extremely useful feature of Watson’s books are her myth-debunking sections. For instance, Watson shares that it isn’t necessary for your soap to reach trace before you pour it into your mold. I have been struggling with swirling for this very reason—I’ve been trying to get all my colors to trace. Another great myth she debunks is that the lye and oils have to be the same temperature before they mix. I had never tried too hard to make sure my oils were at 100° when my lye reached 100°, but so much I had read insisted this step was critical to the point of instructing soapers to have hot water and cool water baths to help reach equilibrium. My soap was turning out fine, so I couldn’t figure it out. I will say that it does seem to be easier to soap if the temperatures are close together, but it’s nonsense that they have to be exactly the same. Watson recommends a range of about 20°F, and that seems right to me.

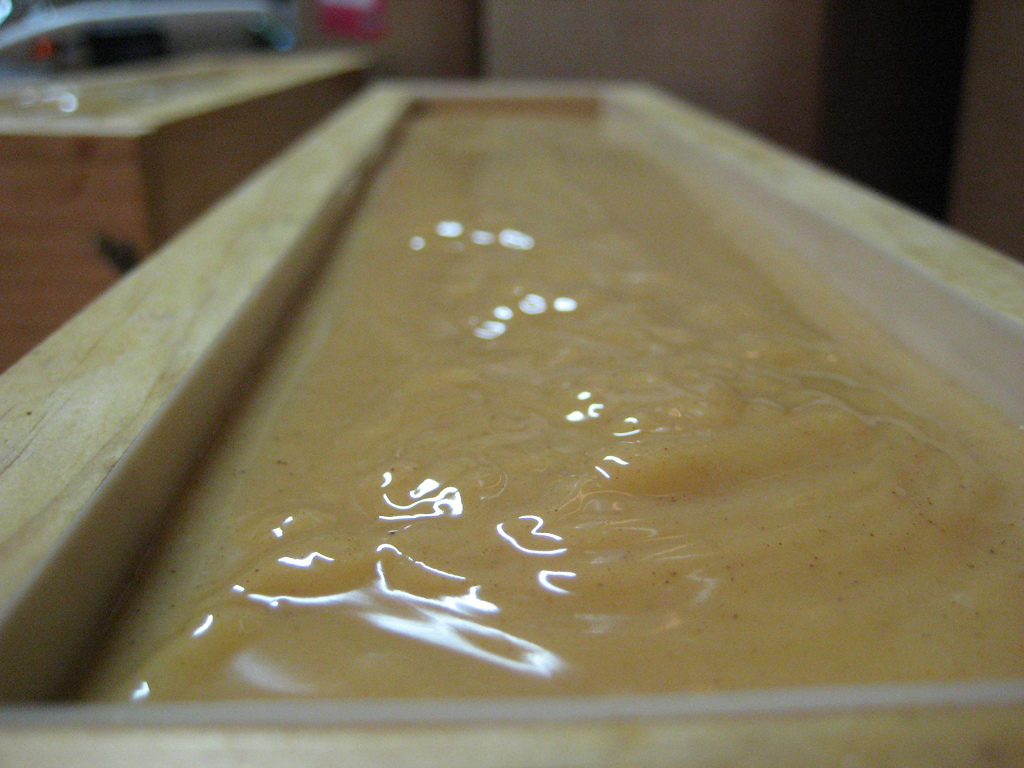

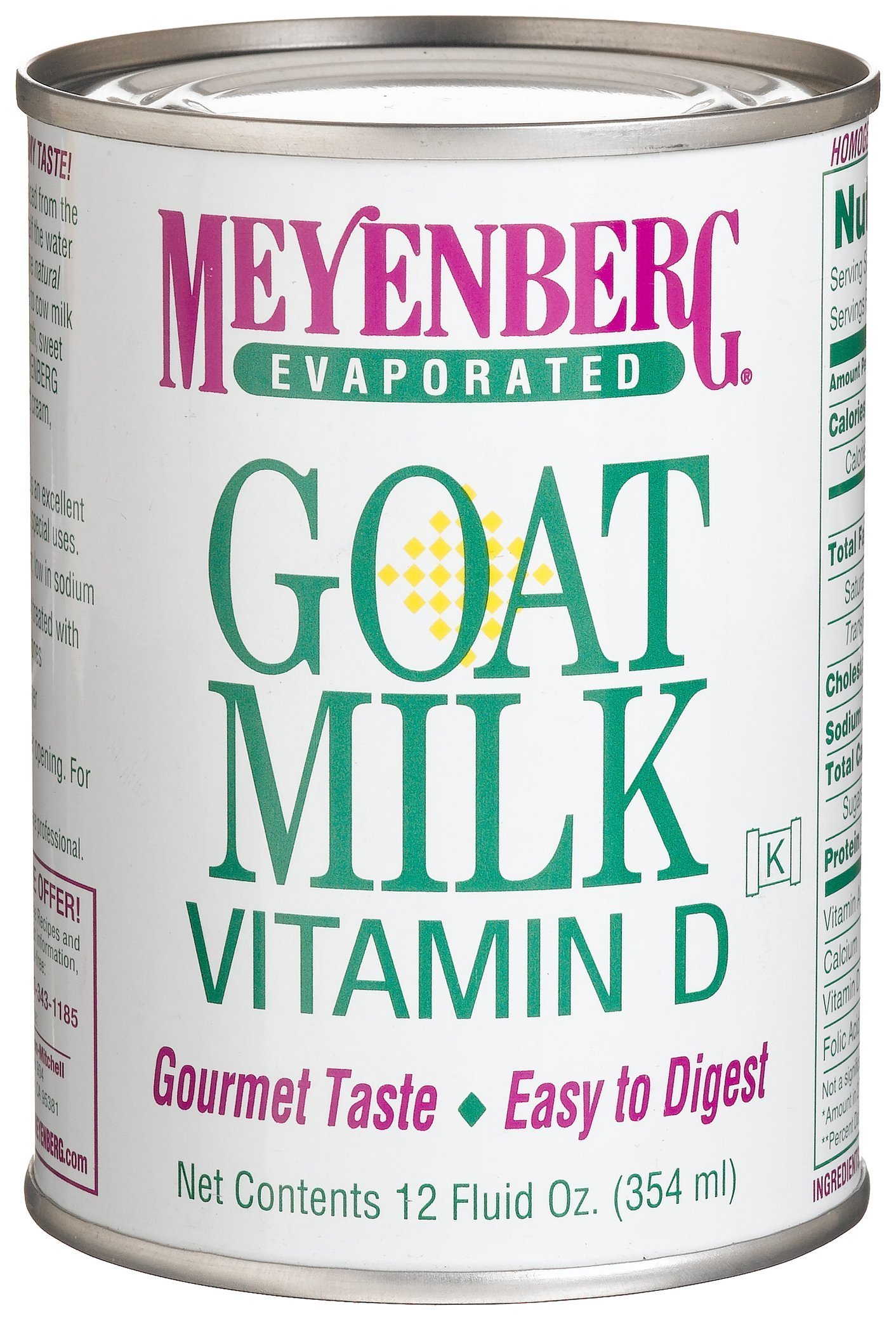

I purchased these books after eying them for some time mainly because I had been having so much trouble with my milk soaps. I made a goat milk bastile that has some lighter spots that look like oil (they are not lye spots), and I don’t know how it happened. I made another goat milk soap that turned into a huge mess. The last soap I made with cream appears to be getting DOS and went through a partial gel. I successfully made soap with cow milk, so I couldn’t figure out what I was doing wrong, and I decided perhaps these books could help me. Watson breaks down milk soap making into two major categories: the cool technique and the warm technique. The cool technique begins with frozen milk, while the warm technique begins with powdered milk. She includes milk-based recipes I had not even thought of, including yogurt, sour cream, and butter.

After purchasing a digital thermometer I call my “temperature gun,” I have come to believe most of the milk soap issues I’m having are temperature-related. I think I’ve been soaping too hot. I have noticed that it seems to be taking longer than usual for my lye to reach 100°. In actuality, I think my thermometer hasn’t been accurate. I have been rigging it to the side of the lye bowl to keep it from falling in, and I think the temperature around the edges is cooler. As a result, I do believe I have been soaping too hot with the milk. I made two batches of soap using the temperature gun to keep an eye on the lye mixture, and both soaped up very nicely. Now that I’ve read Watson’s books and purchased this temperature gun, I feel ready to try milk again.

I wish I had read Watson’s book before I read some of the others because I think I would have trusted myself more. Readers should be aware neither book includes photographs. I have come to believe that good photography is extremely important in a soap-making book, just as it is in a recipe book. Photographs are a baseline you can use to determine 1) whether the soap looks like something you want to make, and 2) how it should turn out. I think Watson’s books were published by a smaller press and may even have been self-published, and photography would probably have been cost-prohibitive. I missed the photographs, but unlike other books with bigger publishing budgets, I was willing to forgive their absence because the information was so clear and helpful.

A side note: I wrote an email to Anne L. Watson asking a question about clean up. Every book I read says wait to clean up for about 24 hours, same as you would to unmold the soap. I didn’t wait the first couple of times because I hadn’t realized you needed to. Then I read that cleaning up right away could gunk up your plumbing, as the soap would saponifiy in your pipes and cause clogs. So I started waiting to clean up, and it was painful. I think perhaps waiting might be a good idea if you have a lot of left over soap, but I only make up what I will use, so I mainly just have a few globs on my soap-making bowl, spoon, and stick blender. And it was a beast to clean up the next day. I asked Watson if this was yet another myth or whether it was a good practice to wait to clean up. She wrote back and said she believes it is a myth. She recommends wiping off excess soap with paper towels and cleaning up with gloves and goggles still on. That makes a ton of sense to me. I am embarrassed not to have thought of it. She also recommends blue Dawn for clean up. So there you have it, friends. Another myth debunked.